We Are in Jeopardy

by Gregory Hicks| Detroit MI 7 Aug 23 10:09AM

It is all coming together, and we are in jeopardy! I am amused by the current discussions connected with various generations of chatbots and advancements in a multitude of technologies including Artificial Intelligence (AI). Of special entertainment value is the discourse on Afrofuturism and its implications for African people into the future. The genre itself is complex and wide in its vision. It ranges from the super worlds of Wakanda to the central question of will and how Africans might exist in the future. In Wakanda we exist, prosper and in fact are in control of our culture, science, government, and our lives. In today’s world we live in narrow valleys of rolling landscapes of economically poor people and in some rare instances, corridors of marginally rich working people who live like they are the royalty of Wakanda. Most of our community experiences involve staggeringly high illiteracy rates, deprivation level economic conditions, limited opportunities, and extremely high rates of human victimization. Somewhere at the pit of our existence we grapple with a multitude of deadlines, situational choices, and emergencies, among which is our interaction with and our treatment by law enforcement…the police.

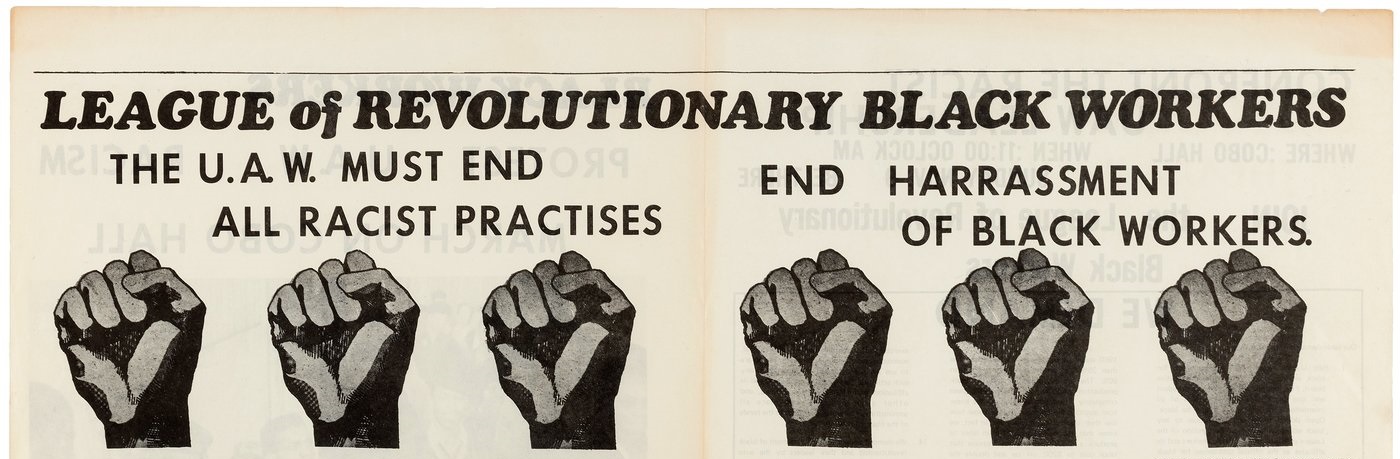

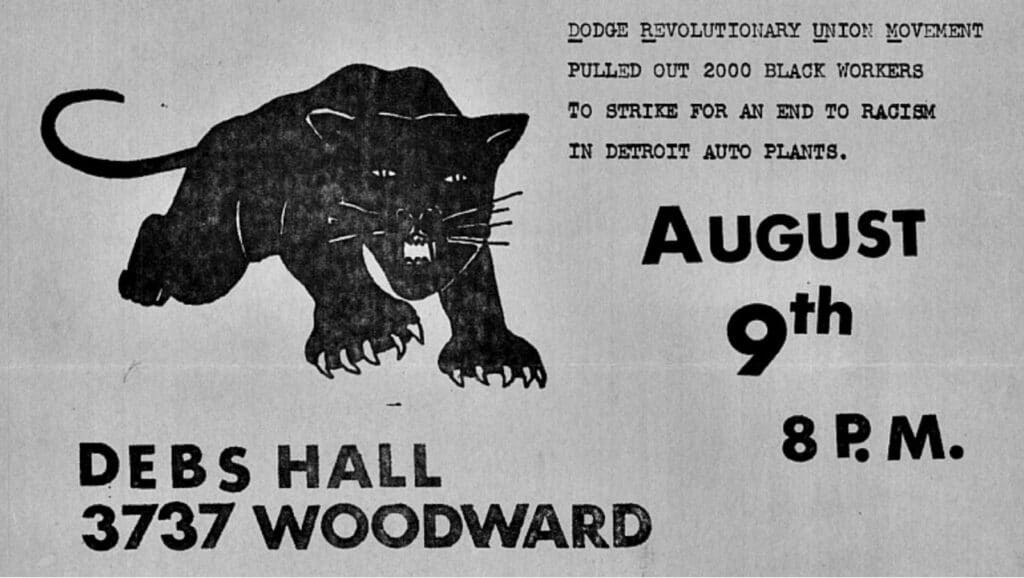

For many of my friends you know of my long practice fighting against oppression, police abuse and exploitation of man by man. In my early years as an activist, we understood that standing on the sideline hurtling insults at the power structure was not sufficient. Our political analysis called for us to understand that Black workers, at the point of production, were central to the economic viability of the nation. If we could grab the attention and organize Black workers, as a social class, we could transform the basic economic and racial relationships in the world. Others thought that the major task was to speak truth to power as a romantic exercise of personal will and individual empowerment. Yes, I admit education and mobilization are central steps to create conscious individuals, but the real power is in collectively organizing large groups to redefine their fundamental relationship within a reimagined social order.

After prolonged strategic battles at organizing, instinctively, the question becomes, what do you do when there is a chance to exercise control? The objective is to capture control over the beast that imprisons you and your community. In my experience between protest and potentially the seizure of actual power (no matter how incremental in its size), I have had to walk a tightly constrained and often confusing path between demonstrations on the streets and a rather slow and sometimes frustrating engagement with policy alternatives designed to correct systemwide concerns. An internal struggle from the inside of the belly of the beast.

As a youngster and activist, on the streets of Detroit, issues were amazingly clear and at the same time extremely complicated. In our view, the bifurcation of critical issues centered around the oftentimes hostile encounters that we had with the police and our isolation, as a racial class, from the local economic mainstream. This was, and I suggest remains, daunting and full of lessons even today.

My first important engagement as an activist was a protest march from Cooley High School to the School Center Building. This 15-mile protest march took about 2 hours to traverse the distance. Our motivation for this and other protest marches was the need to organize around rejecting the purposeful miseducation of Black students. White centered historical accounts of the American experience and hostility of white teachers and counselors as leaders in the classroom fueled our organizing efforts. Untold violent attacks on Black students by whites who lived in the immediate surrounding community of Cooley High added to our imperative to get organized. The atmosphere in the country was rocking from the assassinations of John F. Kennedy, Malcolm X, Martin Luther King, Jr., and Bobby Kennedy. Detroit’s white community was enthralled in the racist antics and politics of Donald Lobsinger, a Father Charles Coughlin – inspired conservative activist who organized violent race-based encounters in northwest Detroit.

Independent of the immediate threats to our lives, enveloped by an atmosphere of white supremacy, our inspiration came from other sources. We openly applauded the fight for national independence of African colonial nations and the impressive African leaders of the day like Amilcar Cabral, Patrice Lumumba, and Kwame Nkrumah. We noted the triumph of Fidel Castro in the small Caribbean nation of Cuba as an inspiration immediately next door and close to our hearts. We read blogs and teletypes from Vietnam that documented the will of the Vietnamese people to challenge and win military battles over the international coalition of western nations that dominated their nation’s politics and economy for decades. Concurrent with these climatic events the overarching style of protest in the United States, much to our disappointment, was to “speak truth to power,” as opposed to “fighting to assume power.”

Equally important to defining the flavor of these times was the great migration of Black Americans from southern hamlets to northern industrial centers. Our migration was a desperate search for gainful employment. A track northward to provide stability in our lives. The push and pull between southern violence imposed on the backs of Blacks and the opportunities for upward mobility was attractive to millions of Black southerners. Our parents were among the first generations that could take full advantage of factory work in the north. Northern city life was preferred over the violence and overt discrimination practiced in the south.

We worked in the plants in and around Detroit, Flint and Saginaw, Michigan. We purchased homes at record levels. We helped to establish a Black middle class that grew its population into majority status within 60 years of its large-scale migration north. All of this progress notwithstanding, we remained the “last hired and the first fired,” and we worked the most dangerous jobs in industries that would employ Blacks. For thousands of Blacks, even these upwardly mobile conditions in the north introduced new types of discrimination all which bread tumult in the lives of our parents. Multiple generations of our people engaged the tumultuous struggle to stay alive and prosper. Black radicals and progressive thinking leaders in Detroit sought many different paths to join the movement for human dignity.

I was there at the impressionable age of 15 years old. Given that I was too young to work in the auto plants and still a youngster in public schools, my path into the movement was as a youth community / student organizer that later linked up with members of a Black adult worker insurgency group demanding reforms from management and the United Automobile Workers. The key issues addressed by this insurgency movement involved adequate union representation of Black workers, fights against “speedups” in the plants, and curtailing automation on the production line by management. These factors and others later added to the displacement of thousands of Black workers and eventually resulted in the realignment of the auto industry and the globalization of automobile production. For us Detroiters, this meant the de-industrialization of our city and the population exodus we experience today.

As we protested in the streets and at the plant gates, the police were brought in to control and halt our organizing efforts. The Detroit of the 60’s and 70’s saw the most wide-ranging protests and anti-establishment movements in recent memory. As we proceeded, organizationally and individually, in our respective lanes of resistance, thousands of us came under the watchful eye of public and private police personnel. One of the most notable of these surveillance operations was the “Red Files.”

According to University of Michigan researchers, the police initiated Red Squad generated the Red Files dating as far back to the 1940’s with the intent to “root out” and “expose” subversives in Michigan. The focus was to intimidate political activists who participated in the labor and civil rights movements, opposed the Vietnam War, or engaged in cultural or social activities judged by police to be “subversive.”

I along with thousands of others had Red Files. Among the falsified information contained in my file was that I often carried a gun, participated as an illegal malcontent looter during the 1967 Detroit Riot, and traveled with a bunch of nefarious hoodlums. In 1967, I was 14 years old and in middle school. This information was crafted by police personnel who created scenarios that best fit their world viewpoint. Their viewpoint was racially biased, militaristic in scope, and replete with white dominating teleological perspectives. Given this file’s description of me and my actions, any police officer would have been justified in shooting and killing me in a chance encounter on the streets. Remember that one of the problems in policing was and remains today a confluence of racial bias, super masculine mindsets, and duplication of overt military practice in our domestic environment.

According to 2018 DOJ statistical reports, 12.5% of male U. S. residents above the age of 16 experience police-initiated contact in one year. Female or other gender-based data were not identified in the report but it is commonly understood that about 3 to 5% of the female population have similar experiences as their male counterparts. Under this mask of data, we understand why we are less engaging and less cooperative with police. We are also less likely to join the ranks of police officers who abuse members of our community. In my opinion, a subculture has formed, sharpened by the realities of constant encounters with law enforcement authorities and the Black community. Abusive treatment by police and the overburdensome financial impact have eaten away at discretionary income in communities of color as they mount a counter push to stop unwarranted encroachments by hostile authorities.

Discretionary resources are required to respond to the increasing dictates of the law enforcement community and the courts. In many cases police and prosecutors are overcharging individuals as they matriculate through the justice system. Families have to mortgage their homes to make bond arrangements or pay attorney fees. Consequently, we are less likely to want to grow up and become policemen. This estrangement between police as workers and the general public is costly in police recruitment, cooperation in crime investigations, and quality of life realities in the neighborhood. To augment this workforce shortage, many departments have enhanced their technology and see surveillance cameras and other surveillance equipment as an extra set of legs and eyes in policing – a force multiplier.

As an individual I have had the good fortune to work and advocate for people in a wide variety of occupations including working to reduce police misconduct. During my employment with the Detroit Police Commission, a civilian oversight agency chartered to be the watchful eye over our local police department, I worked to identify and create reasonable policy-based measures to provide for constitutionally appropriate rules and procedures for our paramilitary forces of the Detroit Police Department. While my stories reflecting community-based struggles to keep police from over-policing regular citizens are many, I want to narrow my focus here to incorporate the issue of advanced technology as a force multiplier. Police force multipliers are any instances where police create an advantage by supplementing their normal capacity with other policing agencies or up-build their impact or watchful eye over the geographic areas where they patrol with the utilization of technology. Cross cooperation with other police agencies increases boots on the ground. Police use of greater technology creates other advantages including greater levels of control.

In techno speak, there is both hardware and software. In general terms, hardware represents the physical stuff and separately, software is the sensory input and communications aspect of the technology. Policing technology goes far beyond the ability to create and maintain arrests and conviction records. The most abusive use of police technology falls in using the technology to predict behavior. In its simplest form, for a machine to predict something the machine must learn about the environment, the characteristics of the interacting elements and finally create a mathematical array to foretell or predict the future.

How do machines develop the ability to predict? Well in short, they do not. They develop the ability to make sophisticated predictions within a degree of statistical assumptions. The process of teaching computers how to think or predict is interwoven in the current discussion of Artificial Intelligence. Intelligence is created by machine learning. The essence of machine learning is presenting or replicating images or translated code sufficient enough that it appears that the machine learns to recognize and sometimes interpret sensory input data.

Take the case of facial recognition. Images or pictures of individual faces are presented as pixelated images and are scanned into memory of the computer in large numbers so that the computer begins to recognize patterns, not people. This process of pattern recognition has had major problems. It started to show real limitations when researchers had exclusive access to pictures of people that revolved around the orbit of the researcher – white men. The computers had considerable difficulty in correctly identifying women and people of color. Clearly to correct this misidentification problem, researchers understood that they needed access to more pictures to enhance the pattern recognition capabilities of the machines as the machine learned how to recognize patterns.

Major tech firms resolved this machine learning issue by creating a personal fascination with selfies. We snapped billions of pictures and posted them on their various platforms, from which they amassed large data sets to train their computers. The second major source of image data came from law enforcement. Federal, State, and local police agencies gave these facial recognition monsters access to an array of law enforcement data that police agencies had been collecting for decades, sometimes legally, but other times like my Red File experience – illegally. This was done without any constraints or rules. Law enforcement agencies began to falsely convince average people of the genius of computer assisted enforcement.

In Detroit, public and private surveillance equipment is deployed through a partnership of local business, cable companies, residential doorbell systems and the police. The green lights in Detroit do not identify pharmaceuticals or marijuana dispensaries, they are surveillance camera locations tied into a network of police (public and private) spying apparatus. The combined tentacles flowing from this police-technology is the largest force multiplier in government.

New technology is not always transparent or understood as it is introduced into government. The Detroit police department purchased facial recognition software under a cloud wherein the oversight agency tasked with looking into the conduct of the department did not discover that the department had and used the software for better than two years after its purchase. In fact, as part of my responsibility to isolate issues, educate, and eventually draft policy recommendations for the oversight board, several Commissioners thought that I was engaged in a process designed to embarrass the Chief of Police, not to explore with them the intricacies of facial recognition and its implications for policing and citizen privacy. By the time this issue filtered up for policy discussions, the boat had long sailed. The department managed to “automate” decades of old police practices and biased attitudes it held about Black and Brown citizens.

The same process of machine learning is associated with broader approaches in Artificial Intelligence. In the law enforcement community, software like geographic mapping of crime or incident reports to establish or identify patterns for machine recognition has already morphed into predictive crime software used to deploy officers and formally charge potential felons and set sentencing recommendations imposed on judges. We need to keep a watchful eye on developing aspects of advanced technological machinery to evaluate their usefulness against principles of democratic engagement, social and economic justice, and fairness across race and gender lines.

To better understand our deep dive into advanced technology, take the examples of AI chatbot software. AI chatbots are said to have the potential to unearth research and writing in academic settings. All the AI software is doing is drawing on historical files along with pulling from broad word pattern recognition databases. The software is making a statistical guess as to what word is more likely to follow other words and phrases. These are illusions based on the frequency of word patterns used in common word usage. Now contextualize this process using the toxic literature associated with race, gender, and class hostilities in this country. We get a mix of exploitation cultivated by historical systems involving race and gender discrimination. In policing, large-scale databases are set to interface with criminal records, investigative records, state driving license and identification data, and a wide range of other data sources from business and privately developed sources.

Our problem is the sad fact that average Americans know few details about the founding of the republic, its connection to colonialization and slavery and all the ensuing systematic patterns of behavior that make us what we are today. How do we as marginally informed consumers judge fact from fiction? Black and other communities of color might stand at the precipice of this entanglement, but all communities are imperiled. Intelligence as seen through the prism of oppressive systems is not actually intelligent. AI is risky and we are all in jeopardy. Automating bias and structural exploitation is not the best future that we humans can create. Wakanda, if ever?

Gregory Hicks is a lifelong student and steward of radical social movements in Detroit. Gregory’s work to end the exploitation of man by man started in middle school and continues until this day. Hicks has worked in a variety of civic engagement, advocacy, and radical organizations and has a Ph.D. in Sociology from Wayne State University. Currently, Gregory Hicks serves on the Detroit Library Board of Commissioners and on the Detroit City Council Reparations Taskforce. Contact for comment: [email protected]

State Repression | Worker’s Rights | Surveillance | Artificial Intelligence | Worker Safety | Civil Liberties

to raise the common issues of the workers and the poor around the world.

in-depth feature

news feed

Socialist Party of Zambia condemns arrest of Dr. Fred M’membe

Dr. Fred M’membe was arrested on charges of libel on August 8, after he was summoned for questioning by the Zambian police. An outspoken critic of imperialist and neoliberal policies, M’membe had long warned of his arrest amid attacks on the Socialist Party

Mali, Burkina Faso, sends delegation to Niger in solidarity

Mali and Burkina Faso’s ruling juntas sent delegations to Niamey on Monday to show unity with the leaders of the coup in Niger amid regional threats to intervene against them.

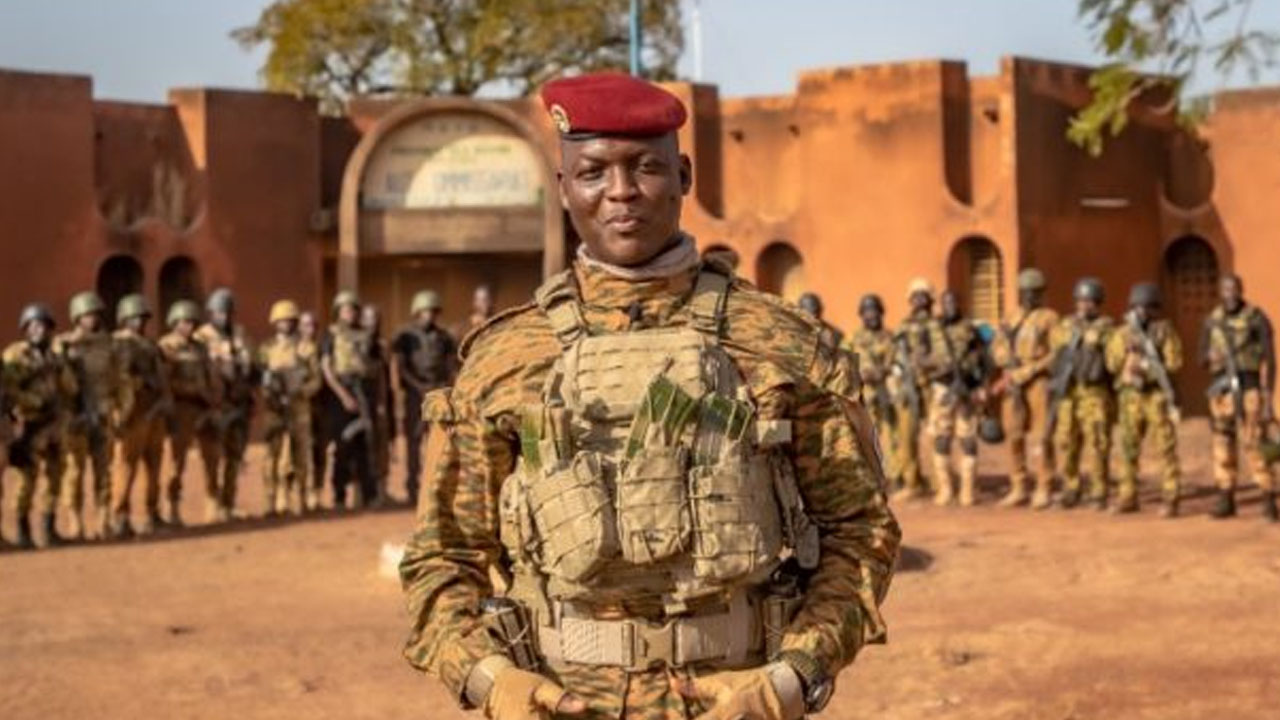

Who is Ibrahim Traore?

Said to have been a shy but intelligent boy in school, Burkina Faso’s Capt Ibrahim Traoré is among the latest military officer to seize power in a coup in one of France’s former colonies in West Africa, now meeting with Russia in a show of rapprochement.

"Kiss the Boer": South African opposition exposes contradictions over anti-apartheid song

South Africa’s liberal, capitalist captured opposition party has wrongly accused its main Left rival of inciting hatred by singing a famous controversial anti-apartheid chant and shutting the door on any broad coalition ahead of the elections next year.

DDOT Bus Strikes, Kills Detroit Woman Outside Government Headquarters

A DDOT bus struck and ran over an older woman with a disability right outside of the Government Headquarters, raising concerns for drivers’ working conditions.

Led by Workers in Korea and Indonesia, May Day Protests All Over the World

Workers demanding economic justice took to streets across the globe to mark May Day, in an outpouring of worker discontent not seen since before the worldwide COVID-19 lockdowns.

The Death of over a Thousand Garment Workers in Bangladesh

Garment workers in Bangladesh fight back against deplorable conditions and work to raise consciousness

Tetsuya Yamagami Hailed A Hero

The shooting of ex-PM Shinzo Abe has blown open secret ties between Japan’s ruling party and the mass-marrying Moonies.

Iguala Mass Student Kidnapping

Authorities admit the state was behind the massacre of kidnapped students from a human rights focused teachers’ college in 2014.

Honduras Garifuna push for state protection

The Castro administration says it will support groups such as the Garifuna, but community members are demanding action.

Sri Lankan Revolution

Sri Lankan environmental policy failures helped fuel people power revolution – Mongabay

EFF: Ramaphosa Must Go

EFF’S Malema calls for Ramaphosa’s impeachment over Phala Phala theft, kidnapping saga – Eyewitness News (EWN)

Hawaiian Freedom Movement

2022 could be a big year for Native Hawaiian issues at the Capitol – Hawaiian Public Radio

Amazon Kills, Workers Fight Back

Amazon employee dies at New Jersey warehouse during Prime Day, Feds probe

Petro-Marquez: Colombia’s Energy Transition

Petro’s and Marquez’s programmoving “from an extractivist economy to a productive economy.”

PetroVictory Consolidates Progressive Wave in Latin America

Petro´s victory in the Colombian presidential election constitutes a landmark – teleSur